One of the key steps to prepare your content and data for AI is developing taxonomies that identify, organize, and define the terms used in the organization in order to better structure and contextualize knowledge assets for use in AI solutions. To this end, it can be tempting to develop one-size-fits-all taxonomies that provide a single account of concepts for the organization. But in some cases, particularly in more complex organizations, the situation may be more nuanced. It may be a step too far to establish a single taxonomy that is identical for all users and uses. A one-size-fits-all taxonomy may not support the realities of applying and using the taxonomy in different parts of the organization.

Example: A sales department in a large organization developed a one-size-fits-all taxonomy to describe their operations, with a goal of improving knowledge asset discovery across all sales roles, including both public and private sector sales. But sales operations were markedly different for public sector and private sector sales. In reality, there were two sales departments which functioned independently; they had completely different processes, offerings, regions, and industries. While they needed the ability to identify knowledge assets that could be shared across sectors, the one-size-fits-all taxonomy could not support that goal: concepts were either too general, biased, or inapplicable to be useful. As a result, search solutions surfaced irrelevant search results, and GenAI solutions used inappropriate sources to generate responses. Sales roles avoided referencing and using the taxonomy. Groups within both sales departments began developing their own splinter taxonomies, to better reflect the realities of their respective operations.

There may be legitimate scenarios where different taxonomy structures, concepts, and/or terminology are needed for different contexts, but a shared taxonomy is still needed to support alignment and coordination. In these cases, taxonomies should be designed to uphold and manage what is different within the organization; care should be taken not to conflate or conceal important differences. This ensures the differences are explicit, referenceable, and usable by users, both human and machine.

Why Design Taxonomies to Uphold Organizational Differences

In some organizations, the design of shared taxonomies may be pulled in different directions as different parts of the organization raise different, at times conflicting, requirements for the taxonomy. These scenarios include:

- Different use cases: Some use cases require different taxonomy breadth, depth, or structure; for example, recommendation or personalization use cases may demand a deeper, more detailed structure, while search and navigation use cases may require a shallower, easier-to-navigate structure.

- Different audience needs: Some users may understand and navigate concepts differently; they may need different structures, depths, and terminology to successfully use a taxonomy. In medical contexts, for example, a heart attack for a patient is one of several specific types of myocardial infarction for a clinician.

- Different domain meanings: Some parts of an organization may have completely, and necessarily, different ways of defining and using concepts. For example, organizations that provide services to both public and private sectors may find their sector-specific functions have different ways of working and, as a result, different ways of describing their processes, offerings, industries, and regional content).

These types of scenarios require special care for taxonomy design. If a taxonomy is designed to strike a compromise across these types of contrasting requirements, then something vital may be lost: one or both use cases, audience needs, or domain meanings will not be adequately supported. A shared taxonomy will not be fit for purpose unless it is designed to support the different demands asked of it.

When to Design Taxonomies to Uphold Organizational Differences

Wherever it is possible to align on a single, shared definition and structure, a shared taxonomy should be designed to reflect that.

Taxonomy deconstruction, defining a set of facets and developing scoped taxonomies to describe distinct aspects of a domain, is especially helpful in this regard. Facets can help breakup complexity to better identify shared meanings. For instance, Document Type taxonomies are best focused on describing the role and shape of information in the document, like a press release or a report, separate from any specific topic, channel, source, or series information, like the name of a recurring report. By defining distinct facets for Document Type and Series Name, it becomes easier to distinguish and manage what is the same (report) and what is different (report series) as distinct facets.

But even after taxonomy deconstruction, it may be difficult to define a taxonomy, or a taxonomy facet, that upholds all of the requirements asked of it. These cases can be identified by considering questions like:

- What is the purpose of the taxonomy? What different use cases will it support? What different audiences will it support? Look for indications that the taxonomy will need to support different requirements for the type, breadth, or depth of structure.

- What is the nature of the coverage? What types of concepts will need to be included? How are those concepts defined by different users of the taxonomy? Scrutinize for any differences in the concepts that need to be covered in support of different use cases, audiences, or functions.

- When and how will the taxonomy need to be updated? Consider any differences in how or how frequently the taxonomy should (or can be) modified to include new concepts or alter existing concepts.

These questions can help identify the types of differences that need to be accounted for in the design of a shared taxonomy. These questions should also be used to consider whether a taxonomy should be shared: if differences are better served with separate vocabularies with light-handed coordination across them, then distinct taxonomies coordinated with an ontology may be more appropriate. The ontology can prescribe a richer set of relationships across the different taxonomies, supporting the balance between focusing each taxonomy on its respective goals and identifying connections between mutual or related concepts across the taxonomies. But if it is necessary to establish a shared taxonomy with a single common set of terms and structure while still navigating key differences, then these questions will also help determine which type of taxonomy structure may best support the different demands asked of the taxonomy.

How to Design Taxonomies to Uphold Organizational Differences

There are a variety of formal structures that can be employed in taxonomy design to help a taxonomy, or a taxonomy facet, meet the varied demands asked of it. These formal structures include: controlled vocabularies to specify what terminology to use; taxonomy structures that organize concepts in hierarchies and categories; and thesauri that identify terminology variants and related concepts. Each of these formal structures ensure a logical, consistent, and SKOS-compliant approach for interoperability, usability, machine-readability, and manageability over-time. As a formal structure, it supports the standardization and alignment required for the semantic layer by identifying and relating concepts used within the organization.

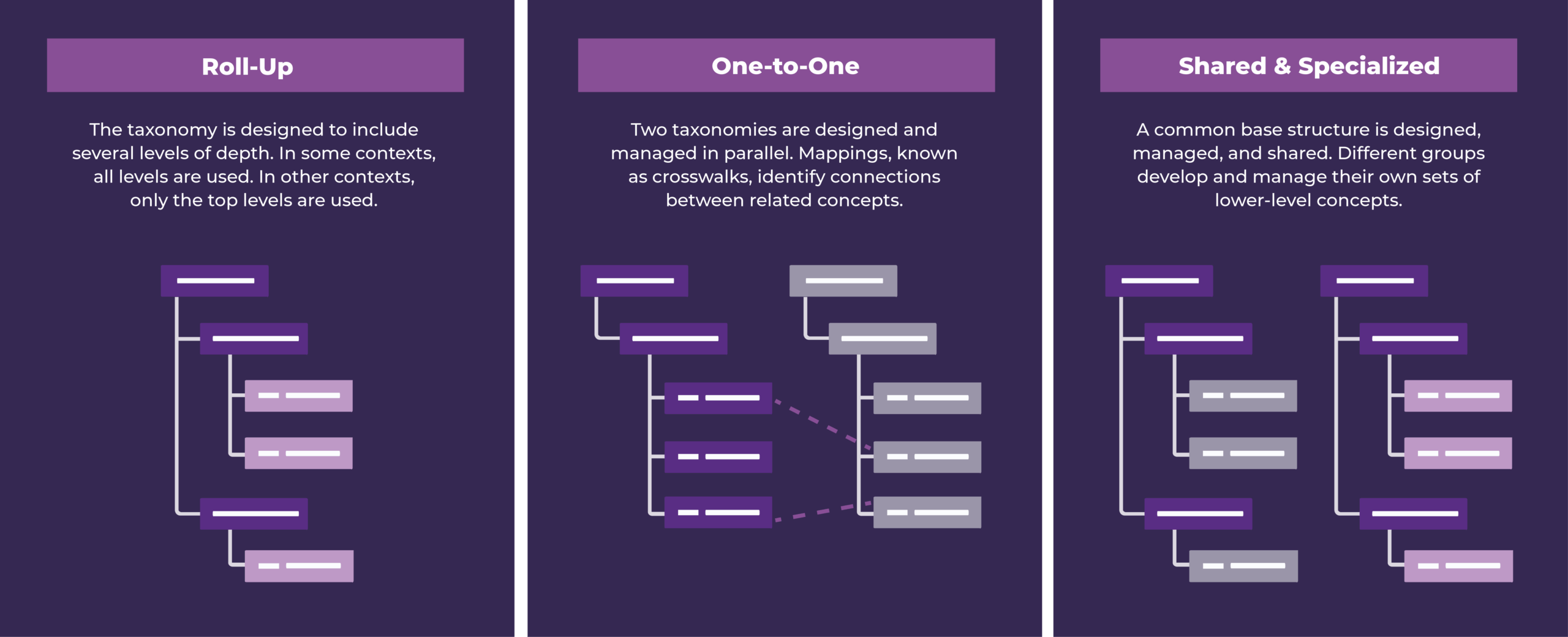

Here, we’ll focus on designing taxonomy structures that organize concepts into hierarchies and categories that are meaningful and actionable for different types of organizational requirements. Here are three examples of taxonomy structures that formally capture and uphold different organizational requirements: Roll-Up, One-to-One, and Shared & Specialized.

Table 1: Types of taxonomy structures

| Roll-up | one-to-one | shared & Specialized |

|---|---|---|

| What it is: A single taxonomy with several hierarchical levels. All hierarchical levels are used for some use cases. But only the top hierarchical levels are used for other use cases. Like an accordion, the taxonomy can be stretched out or condensed, as needed. | What it is: Two taxonomies maintained in parallel. A set of crosswalks or mappings is defined to identify equivalent, or approximately equivalent, concepts between the two taxonomies. These mappings may be managed in a taxonomy management tool or using an ontology, depending on the use cases involved. Like a street crosswalk, there are designated places for connecting concepts, or safely crossing, between taxonomies. | What it is: Two or more taxonomies that share the same set of higher-level concepts, but they need to include different lower-level concepts. Like a basic muffin recipe, there’s a standard starting point for making a plain muffin, to which you can add more specific flavors, additions, or toppings. |

| When to use it: The Roll-Up structure supports offering different levels of granularity for different contexts. It is a good option for a taxonomy that needs to provide access to more granularity in some contexts and less granularity in others. This includes any AI solutions with use cases that are better supported focusing on higher-level concepts, rather than using the exhaustive detail of the full taxonomy. | When to use it: The One-to-One structure is best when very little is shared between how concepts are defined and organized in different contexts. In these cases, concepts need to be distinctly represented for each context, but we can still identify the specific concepts in the taxonomies that address similar concepts using crosswalks. AI solutions can benefit from referencing the taxonomy relevant for respective contexts, to better identify the set of concepts and terms that are relevant. The mappings can also be referenced to identify explicit cases where concepts in distinct taxonomies are similar. | When to use it: The shared and specialized taxonomy structure is best for supporting different variations within a similar domain. There is commonality in the types of things we are describing; in other words, there are some core, common concepts. But there are differences in what lower-level concepts are relevant for different contexts. This can support different AI use cases, either by referencing the rolled-up taxonomies to focus on what is common or by referencing the specific taxonomy variation that is relevant for its respective context. |

Table 2: Examples of taxonomy structures

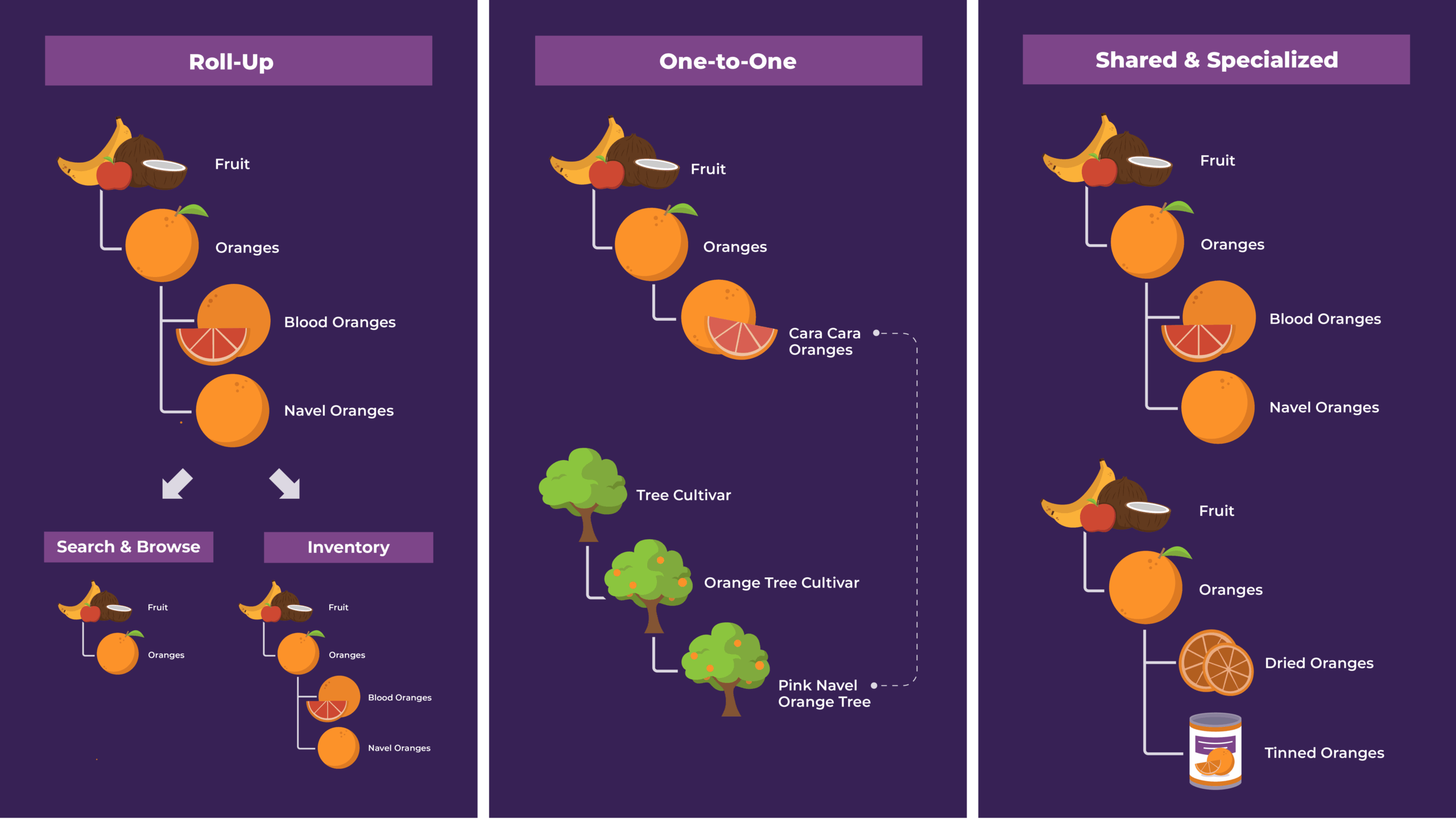

| rolled-up Example | one-to-one example | shared & Specialized example |

|---|---|---|

| In browse and search experiences, grocery shoppers want to look for types of Fruit like Oranges generally. But produce managers want to track each type of orange, like Navel Oranges or Blood Oranges, currently in stock. With a roll-up taxonomy, the first two levels may be displayed in browse and search experiences, whereas all three levels may be used for inventory use cases. | Orange sellers and Orange growers may not use Orange concepts the same way. Orange sellers use common names, like Navel and Blood Oranges, and group all orange types together. But Orange growers may use the names of tree cultivars to identify the Oranges they produce. These two taxonomies can be defined and managed in parallel, with a crosswalk to identify that Cara Cara Oranges in the seller taxonomy maps to a Pink Navel Orange tree cultivar in the grower taxonomy. | Oranges may be sold in the store as either produce or non-perishables. A shared and specialized taxonomy could be used to define a common base structure, Fruit > Oranges. The produce department includes lower level terms under Oranges for types of fresh oranges, like Navel Oranges and Blood Oranges. The non-perishable department includes lower level terms under Oranges for types of preparation, like dried, candied, or tinned Oranges. |

Conclusion

These taxonomy structures all aim to align and manage a common set of concepts within an organization, despite different requirements in what concepts need to be included and how those concepts need to be structured and used. They should be used when a common taxonomy needs to be defined and shared. The most appropriate structure will support the particular differences that need to be managed and the particular outcomes that need to be achieved.

By formally capturing organizational differences in a shared taxonomy, an organization can establish a representation of the business domain without obscuring or minimizing differences. Importantly, this provides a formal record of the concepts that are relevant for specific parts of the organization and how they define and use those concepts. This is essential for supporting the realities of the business. It is also essential for providing an accurate depiction of the business domain for AI solutions. GenAI solutions, for example, can struggle to navigate inconsistencies in how concepts are used across an organization’s knowledge assets and produce hallucinations, as a result. By clarifying and structuring those concepts with a taxonomy, we can help make those differences explicit and traceable, such that, a GenAI solution can produce more reliable, consistent results.

Contact EK if you have questions on how to establish a shared taxonomy, or how to adapt an existing shared taxonomy, to better uphold key organizational differences.