Introduction

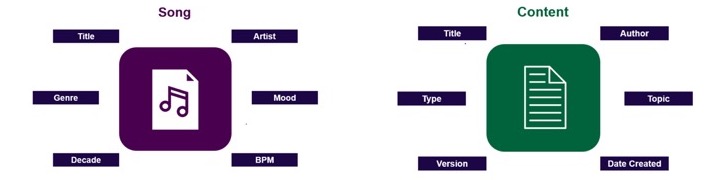

As a big music fan I am always on the hunt for new and better ways to organize my personal music library. Some days it makes the most sense for me to make a playlist for a specific activity, like exercising or resting, while other days I want music from a specific genre or artist. Every song has different facets: artist, genre, decade, mood, tempo, and more. There are so many ways to group songs together and such a vast amount of music out there that at times I have to remind myself that just because I can classify music a certain way, doesn’t mean it makes any sense for me to do it.

As a taxonomist, I often encounter a similar dilemma. I work with clients all over the world to construct intuitive and effective taxonomies with the goal of increasing the findability of their content. One of the initial steps in the design process is determining, through stakeholder interviews and content analysis, what set of facets, or metadata fields (usually no more than 5 or 6), are the best to start with. For a comprehensive overview of all the steps involved in creating a taxonomy, check out my colleague’s blog series “The 4 Steps to Designing an Effective Taxonomy” here.

Choosing Facets

When I start working with a client, one of the first orders of business is determining which facets of content are important to their users. Typically, I can rely on a few initial metadata fields, like topic and type, to guide conversations and analysis, but beyond that, each organization values something different about their content. I have worked with software engineering teams who wanted to search by the coding language of the documentation they were looking for and government agencies who put a premium on sensitivity of the content. Taxonomies that are the most intuitive and useful to users will begin to take shape as the specific needs and functions of an organization are uncovered.

These initial stages of taxonomy design can be challenging, so to help guide the way, the following are a few of the approaches I’ve learned from the numerous taxonomy projects I’ve worked on.

First, look at the content through the eyes of the users in your organization; what role do those users play? Every job role and functional area at your company will have metadata that is relevant to them. This is often what ultimately makes a taxonomy unique. Consider my earlier story about making music playlists. As a music listener, facets like genre and artist are important to me. But what about a DJ, or a sound designer producing the soundtrack for a movie? These roles cause people to interact with music differently, just as job roles can change a person’s relationship with content. If your company is full of DJs, it might make more sense to create a taxonomy for the tempo, or beats per minute of songs, even though a typical music listener would seldom consider such a factor.

Second, keep in mind that two of the most important benefits of a taxonomy, findability and discoverability, are often derived via faceted navigation. What aspects of content would be helpful for users to sort and refine content? A sound designer creating the soundtrack for a movie that takes place in the 1970s would be able to do their work more efficiently if they could search for music by the year it was made. Conversely, a music listener like myself might care less about the decade the music was produced, and more about whether or not it is a part of a genre I enjoy. Ask your users what facets of information they wish they could search for content by. This input will be valuable in determining what taxonomies should be developed and how these taxonomies can best be implemented.

Finally, examine the content itself. With what types of content are your users interacting? If your organization produces a lot of one specific type of content, what metadata makes the most sense to include with it? An acoustic/electric facet might be useful in a music library that only contains guitar music, but not for a library with rap music. This was something I encountered when working with a team of software engineers to develop a taxonomy that would provide a common thread when working with their many global teams. The type of content they most frequently worked with was software documentation, the characteristics of which are very different from the metadata that is typically captured for more ubiquitous content like policies or guides. In response to this we had to include metadata around coding language, specifications, and applications in the taxonomy, as opposed to more traditional fields like topic and functional area. The body of content you are working with will tell you a lot about what metadata is important.

These are just a few approaches to beginning your taxonomy design journey. Other factors, like secondary taxonomies and permissions allow for an even better content experience, and might come into play further down the road. If this something you’d like to speak with the experts at EK about, reach out to info@enterprise-knowledge.com.