When your taxonomy has overgrown your path towards usability, it’s time to do some gardening.

When your taxonomy has overgrown your path towards usability, it’s time to do some gardening.

Congratulations: you have a taxonomy! You’ve gone through the work of gathering user feedback, developing a design, validating the design, and you’ve come out the other end with a stable set of terms. Maybe you’ve only just completed your efforts, or maybe you’re working with a legacy system. Either way, you’ve done it. Time to rest on your laurels.

Only…now that you have it, the taxonomy doesn’t really seem to be working for you. Maybe it turns out that five separate levels of hierarchy devoted to the technical differences between slippers and slip-ons can’t be implemented in the current version of your content management system, and now they sit unused in an Excel sheet instead. Or you’re hearing from content authors that some subjects have so many terms that they struggle to reliably choose the correct tags while other subjects struggle from a lack of terms and ambiguity among them. Maybe this taxonomy worked fine years ago when it was first implemented, but it has gradually become more and more unwieldy and difficult to manage year after year.

Whatever your situation, you’ve reached the point of crisis. What was once or what could have been a well-tended garden of terms has become an untamed forest of thorns. What now? This blog post will take you through some of the common problems with thorny taxonomies and solutions for turning your frog back into a prince.

Problem 1: Too Many Terms

- Too many terms to choose from.

- Some terms with very little uptake and use.

- Likely ambiguity in spite of this proliferation of terms.

When creating a taxonomy, we want to gather and process as much input as we can to inform the ultimate design. As a result, it might seem like a taxonomy with more terms is inevitably better than a smaller taxonomy on the same subject. However, this isn’t the case. The greater the number of terms you have, the greater the tradeoff you’re making in regard to usability. Now, there are use cases in which you would want a larger taxonomy; for example, taxonomies developed for machine learning, auto-tagging, and natural language processing all require a high level of granularity. In contrast, taxonomies developed for search and navigation should seek to be broad and intuitive for a wide range of users. For enterprise taxonomies, you want to look for areas of compromise and “best fit” rather than aiming for perfect coverage in your design.

So, what should you do?

Solutions:

Consider how your taxonomy is going to be used – do you want a broadly comprehensive taxonomy for search, or a taxonomy made to tag a large corpus of documents with high detail? If you’re tracking metrics on the current use and application of your taxonomy, look at the terms that are used the least. Are the concepts these terms refer to already covered by other areas of the taxonomy? Terms that are already covered can become synonyms of related, more commonly used terms, or removed entirely. Are they ambiguous? Ambiguous terms can be removed or replaced with a more specific term. Alternatively, you might want to consider enhancing an ambiguous term with a scope note. Especially in specialized vocabularies, it may be that what appears to your taggers as an ambiguous term has, in fact, a specific industry or field definition that they are unfamiliar with. In this case, it may be enough to define the term rather than removing or replacing it.

Problem 2: Hierarchy and Balance

- The bottom terms of your taxonomy vary widely in regard to specificity.

- Some branches of the taxonomy are 5 or more levels deep, while others bottom out at 2 or 3 levels of hierarchy.

- The most used terms tend to be hidden behind several layers of categorization.

- Project teams that contributed the most to the taxonomy effort have far more defined branches of the taxonomy.

Take stock of how many layers of hierarchy your taxonomy has, versus how many it needs. In general, because an enterprise taxonomy will be used by people with a variety of subject backgrounds, we aim to keep an enterprise taxonomy to 2-3 levels deep to promote usability. More specialized vocabularies or advanced use cases may require further hierarchy. Hierarchical or parent-child relationships are a powerful tool for distinguishing between different concepts, and they are what differentiates a taxonomy from a flat list of terms. Implementing that specificity comes at a cost – the more levels of hierarchy you require users to understand and navigate, the greater the complexity and difficulty they will encounter when searching for a specific term.

So, what should you do?

In some cases, it may help to move up branches of the taxonomy that are at a lower level of hierarchy in order to make them easier for users to apply and find. It can be counterintuitive, since this move may involve moving terms out of categories that they would otherwise fit into. The focus should be on striking a balance between accuracy and usability.

If you have a few lower branches of your taxonomy that are notably more specific and relate to a particular project team or work area, you should also consider whether you would be better served by moving these branches into a secondary taxonomy that can then be used in conjunction with your original taxonomy. A secondary taxonomy applies to certain types of content within a narrow focus area, and is an excellent method of providing further granularity for teams that require and can make use of it. After moving these terms out of the original taxonomy, you may then fill their area of the taxonomy with a few more general terms that better match the specificity of the rest of your taxonomy.

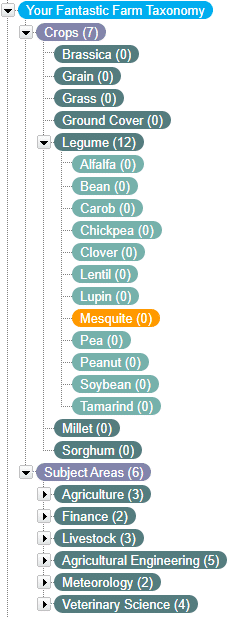

For instance, looking at the example of a farming-related taxonomy in the image to the left (Your Fantastic Farm Taxonomy), suppose we want to tag documents related to farming. Most of the documents fit into a general subject area, but a subset is specific to individual crops. Let’s say that our users want to be able to find the documents they need related to the crop they’re planting. Rather than unbalancing our taxonomy by placing all of the crop information under Agriculture, where it would be difficult to discover and unusually large relative to the taxonomy as a whole, we can pull out crops into its own category instead. This results in a taxonomy that is easier to apply and navigate.

Finally, read through the terms of your taxonomy with an eye toward consistency. If you’re not looking to implement auto-tagging immediately, it’s fine to have some mix of general terms (i.e. Car → Toyota) and specific terms (Silver Toyota Camry 2009). But if there are areas marked by specificity, such as using product and program names, or individual items of a class rather than the class, consider making the existing terms synonyms and finding either newer, more generalized class terms or just going with the next highest level of terms instead.

A Note on Faceting:

You may know the old phrase, sometimes attributed to Benjamin Franklin or Samuel Johnson: “A place for everything and everything in its place.”; or the taxonomist’s version: “Mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive”, also known as MECE. When creating a taxonomy, it can be tempting to search for that perfect place for each and every term. Inevitably, however, you are going to come across instances in which a term could conceivably belong to two very different branches of your tree. There are several routes you can take when this happens:

- If your system supports it (more on that in a moment) you can use polyhierarchy to place that child under two parent terms.

- You can try to make the two instances of the term more specific, in order to distinguish them from one another (Milk (Agriculture) for milk as relates to farming vs Milk (MNCH) for milk as relates to maternal and neonatal child health, for instance).

- You can make a choice and remove the term from one of its two parents. This will obviously affect the use case that isn’t chosen, but is easier to handle from a system perspective.

What I would suggest though, is to consider faceting. A faceted taxonomy is structured such that the user is expected to combine multiple terms when searching/filtering. This is especially common in product taxonomies – think of Amazon. Rather than having a hierarchy of terms that eventually leads to “red ball,” there would be a branch of color descriptors and a separate branch of toys, with the expectation that a tagger would apply both “red” and “ball” as separate terms to describe a red ball. Faceting is well-matched to the search behaviors of non-experts, and a powerful option for balancing your taxonomy.

Problem 3: Systems and Training

- There is confusion over how to apply terms, or a disconnect between your current users and the groups that gave input on the taxonomy.

- The taxonomy is implemented in several systems, with slight differences between each implementation.

- There are differences between the “master” taxonomy and the system implementations.

In discussing a taxonomy, it’s important to consider not just the terms and the relations between them, but the systems in which the taxonomy is instantiated. You should consider:

- How many levels of hierarchy can the target system hold and display?

- Is the taxonomy contained and managed centrally, feeding into various systems and keeping each system up to date, or is it scattered across the enterprise in various conditions?

- How do new and existing users learn to use the taxonomy?

Problems in any of these areas will adversely affect the usability of your taxonomy and your ability to manage it long term.

So, what should you do?

Make sure that your taxonomy is designed with implementation in mind. If there is limited support for hierarchy in your target system, then there are a couple of avenues for adopting your taxonomy. You can turn lower-level terms into synonyms of their parent terms, and display only the parents. Or you can look into faceting, and implement your taxonomy as a series of flat vocabularies that can be combined for greater specificity.

You may also want to look into using a Taxonomy Management System, or TMS. This is a tool that can centrally manage your taxonomy and feed it to target systems. Standard TMSs will have features to aid in the management and quality checking of your taxonomy, and may also have auto-tagging, corpus analysis, and other capabilities. One of the biggest advantages of using one, though, is keeping your taxonomy updated and in sync across systems. Allowing different implementations of your taxonomy across systems and differences in terms can lead to user confusion, driving low adoption and a failure to use your taxonomy effectively.

Training is another system-related aspect of your taxonomy. Instructional documentation around term definitions, how to apply them, and mechanisms for providing feedback all help to improve tagging accuracy. Maintaining documentation around taxonomy sources, updates, and changes over time is also important for avoiding confusion within the long-term health and management of the taxonomy.

For the Future

Once you have a good working taxonomy it’s important to ask yourself what you can do to avoid problems in the future. A well-managed taxonomy will be a tool for findability, analytics, and alignment for years to come, while a poorly-managed one will fail to support its use cases and actively cause confusion. So what can you do? How do we defeat the expiration date on your taxonomy?

Once you have a good working taxonomy it’s important to ask yourself what you can do to avoid problems in the future. A well-managed taxonomy will be a tool for findability, analytics, and alignment for years to come, while a poorly-managed one will fail to support its use cases and actively cause confusion. So what can you do? How do we defeat the expiration date on your taxonomy?

The answer is to turn to the unsung hero of taxonomy and KM efforts: governance. Creating a KM-governance structure with stakeholders from across your organization’s taxonomy users is the best way to maintain and adapt your taxonomy over time. Admittedly, this is a tempting step to skip – after all the work that goes into creating the taxonomy, it can be hard to muster the energy for the long-term work of maintaining and adding terms. However, governance work can be one of the most valuable KM duties if you give it the necessary attention. Finding areas of alignment and compromise across the enterprise is a challenge that not only improves your taxonomy’s quality, but also forces you to develop a greater understanding of your institution and build connections across teams. A great governance structure is the secret weapon to keeping and using a strong business taxonomy. You should have approval processes for major and minor changes to the taxonomy, and meet regularly to discuss proposed changes.

Conclusion

I hope that this article helps to provide a first step if you are struggling with an untamed taxonomy of your own. Enterprise Knowledge has many taxonomy, ontology, and KM experts well-versed in problems across many organizational contexts, and we are happy to partner with you at any stage of your taxonomy journey. Contact us to learn more.