What does the term ‘faceted navigation’ call to mind? For search-savvy individuals, it’s a search experience similar to that which you would find on Amazon. Facets primarily allow an individual to quickly sort through large amounts of information to locate a single or few entities. In a world dwarfed by the amount of data it produces, faceted navigation answers the universal need to narrow.

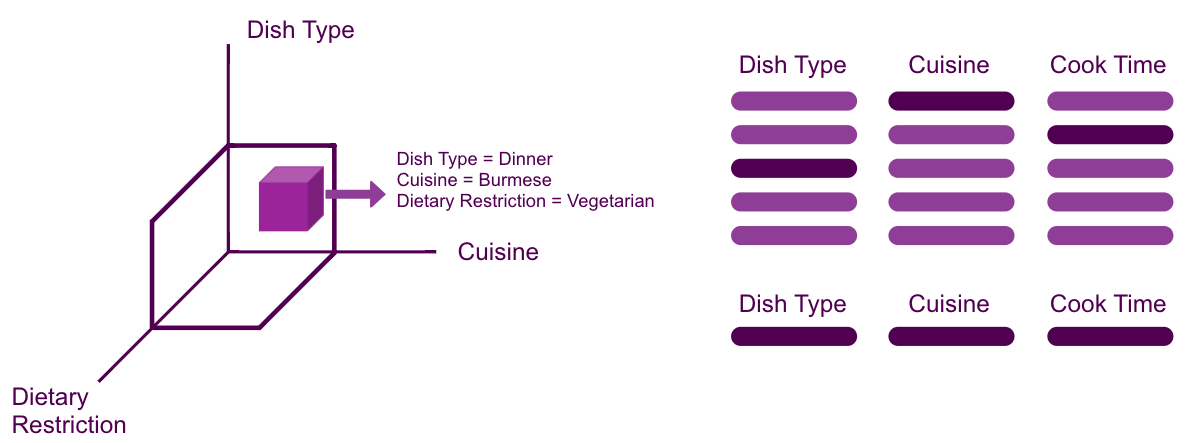

Ultimately, faceted navigation is a condensed and simplified manner of answering a string of Boolean questions. Take a cookbook, for example. If all recipes are organized by dish type (breakfast, lunch, dinner, snack, dessert, etc.), you can easily find a recipe that satisfies the desired dish type. In faceted navigation, this decision process would look like this:

- Breakfast? No.

- Lunch? No.

- Dinner? Yes.

- Snack? No.

- Dessert? No.

When ‘dinner’ gets a ‘yes’ and all other dish types get a ‘no,’ then you’ve limited the number of recipes in which you’re interested. Though because there’s still a number of recipes to consider, there are additional opportunities for refinement. What type of cuisine are we interested in?

- Burmese? Yes.

- French? No.

- Indian? No.

- Italian? No.

- Japanese? No.

Now we’ve shortened the list of available recipes again. At this point, the only results that remain are both considered ‘dinner’ and ‘Burmese.’ Within the food realm, there are a number of ways to continue refining the results. You could filter the recipes by dietary restriction (vegetarian, pescetarian, vegan), cooking method (slow cooker, grill, sous vide), cook time (15 minutes, 30 minutes, 1+ hours), and so on.

There are, of course, multiple ways to locate the target document. Faceted navigation does not demand ordered narrowing, nor does it require that you know exactly what you’re looking for. It’s a means of completing the advanced search process through user-led interaction with the information.

With faceted navigation you can display information from multiple libraries, allowing your user to see all information grouped by its relevant types. In contrast, a folder structure limits your means of storing and viewing information as folders allow for only one type of grouping. Additionally, folders don’t cater to the various user-based approaches to locating information, as these approaches are largely informed by the user’s professional background, their search preferences, and their role within the organization. Comparatively, a metadata-backed search process accommodates a multitude of approaches while guaranteeing a common level of success. For an in-depth exploration of the pros and cons of using both folders and metadata-backed search, see the ‘Folders v. Metadata in SharePoint Document Libraries’ article.

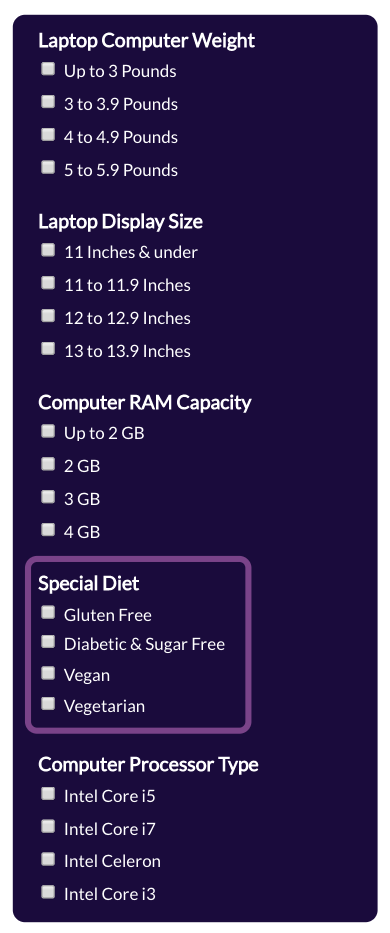

Facets physically ‘live’ within the search results, typically on the left side of the web page. The facets bar can be likened to a custom map: it’s ‘custom’ because, from the outset of your search query, the facets are categories specific to the keyword(s) in that query. When searching for a computer to buy, perhaps your query resembled the following image:

You would expect to be able to narrow down your results by display size, RAM capacity, and processor type. And while a facet for ‘Gluten Free’ would be nonsensical when searching for a laptop, it’s a desirable option when looking for a cookbook.

You would expect to be able to narrow down your results by display size, RAM capacity, and processor type. And while a facet for ‘Gluten Free’ would be nonsensical when searching for a laptop, it’s a desirable option when looking for a cookbook.

Faceted navigation allows you to find what you’re looking for more quickly, while also providing greater context to your search. As a whole, the facets themselves function as a multi-dimensional understanding of searchable content and can highlight inter-content relationships. For example, in reference to the image on the left, ‘Up to 3 Pounds,’ ‘3 to 3.9 Pounds,’ ‘4 to 4.9 Pounds,’ and ‘5 to 5.9 Pounds’ don’t mean or refer to anything specific without their ‘parent’ identifier of ‘Laptop Computer Weight.’ And vice versa, ‘Laptop Computer Weight’ isn’t a useful search facet without its ‘children’ that inform the user of the existing limits of that facet.

Employing facets in your search experience effectively capitalize on the user-dependent decision-making process. As explored above, each user relies on a different search approach uniquely informed by their own background and preferences, and facets allow for that approach to be employed, while guaranteeing a degree of success regardless of the approach style.

Of course, faceted navigation isn’t just a tool for finding recipes or buying laptops. It also holds significant value for internal purposes, like intranets and knowledge bases. In these cases, the facets are powered by an organization’s own taxonomies, where filtering is fueled by the natural vocabulary an employee would use to specify what they’re seeking. Common metadata fields for internal systems include topic, information type, audience, and source, but every organization is unique and should invest in the design process to identify the right fields that will guide their end users.

Facets can also reveal patterns existing within your information, something I will explore in my next blog post entitled ‘Pattern Discovery through Facets.’ This post is an introduction to how facets can improve item and document findability. Other factors, like customized action-oriented results and an enterprise-wide taxonomy, allow for an even better search experience. If this is something you’d like to speak with the experts at EK about, reach out to info@enterprise-knowledge.com.