The rate at which we are producing new information is unprecedented. Each year our ability to capture and create information becomes easier. As a result, the need to find information becomes more and more important. Designing the structure of information environments (intranets, websites, digital libraries, etc.) in a way that promotes the findability and discoverability of content is critical. When users cannot find the information that they need and are unable to locate information they didn’t previously know existed, the information created is wasted, innovation is stifled, and duplication of effort is highly likely.

Taxonomies are one tool that can be leveraged to organize information environments by providing a consistent controlled vocabulary that allows content authors to label content like documents or web pages consistently. This ensures that content will be surfaced correctly in search results and that each information item will appear correctly in navigation menus. As a professional Information Architect and Taxonomist, I frequently see poorly designed taxonomies. One common taxonomy design error is the use of overly specific language that does not align to content. This means that the vast majority of content contained in the information environment cannot be easily mapped to the taxonomy and the terms contained in the taxonomy are not easily understood by end-users. One way I avoid this pitfall is by applying the Five Laws of Library Science when designing a taxonomy. The Five Laws of Library Science were proposed by S.R. Ranganathan long before the introduction of intranets and websites. Although the focus of these principles was on operating a library system, I believe that applying Ranganathan’s original principles leads to a more usable digital environment and a taxonomy that is directly aligned to content. Since its publication in 1931, the Five Laws of Library Science have made a tremendous impact on library and information professionals. In my opinion, these laws should be carefully considered when investing in your intranet or designing your next taxonomy. This blog is seeks to provide an examination of the following:

- S.R. Ranganathan’s Original Five Laws of Library Science;

- The application of each law in today’s digital world; and

- The business value each law provides in today’s digital world.

Books are for Use

The first law “Books are for Use” means that books should not be hidden from library patrons. Libraries serve humanity byproviding knowledge and ensuring it is accessible. The first law of library science is directly related to the design of taxonomies in digital environments. Taxonomies, when integrated with intranets, websites, digital asset management systems, or digital libraries, provide access to content. Digital content like physical books offers knowledge to end-users. When designing taxonomies, our word choice and position in the hierarchy should be carefully selected with the end-user in mind. The purpose of our taxonomy should always be to serve end-users by ensuring the knowledge and information we are describing is easily accessible.

This law also goes beyond taxonomy design. Too often when we implement security permissions in a digital environment, we create overly restrictive permissions preventing end-users from accessing content that they need. By applying this law to our taxonomy development process and the development of access rights, we can work towards putting our content to use.

Today, the value of this law translates to increased innovation and reduced duplication of effort. If content is not thoughtfully organized in a way that promotes use or even worse, if content is inaccessible due to overly restrictive permissions, end-users do not know that the content exists. This means that content does not serve its purpose, leading to potential duplication and loss of innovation.

Every Reader His/Her Book

The second law of library science denotes libraries exist to distribute knowledge to a variety of different patrons. Librarians should not judge the patron’s reading material and seek to serve all. This is as relevant today as it was in 1931. When creating a taxonomy, we should not design taxonomies to suit the needs of a select group of individuals. Every user has content that they need to access. The taxonomy should always seek to serve each user group. By including each user group in initial research and validation, we can break down information silos and promote the inclusion of a diverse array of content. Adherence to this law will improve morale and contribute to a productive company culture through information access providing real business value.

Every Book His/Her Reader

The third law Ranganathan proposed is “Every Book His/Her Reader. This means that each book in the library is useful, regardless of specificity or how small the groups seeking the book may be. In the digital age, our purpose as Taxonomy Designers and Information Architects is to make information accessible. The third law is directly applicable to designing the structure of an information environment. Clients often ask if specific content items deserve taxonomy terms to describe them. Following the Third Law of Library Science, as long as the information item is not being deprecated, the taxonomy should describe each content item. Following this law ensures that each information item is labeled and categorized. This offers a positive user experience for all end-users and ensures that content can be easily surfaced no matter how specific in the event of a legal event or crisis.

Save the Time of the Reader

The fourth law of library science, states that each person should be able to locate the material they desire quickly and with ease. In the digital age, we should carefully analyze the type of knowledge organization system that we believe will allow end-users to find content the fastest. Although each knowledge organization system has its pros and cons, in many cases we find that a faceted taxonomy is the preferred knowledge organization system. Structurally, faceted taxonomies allow individuals to quickly find content items by simultaneously searching and browsing. We also need to incorporate language in the taxonomy that resonates with the group who will ultimately be seeking the information we are describing. Combining relevant language and a knowledge organization system that promotes ease of access, ensures that we are saving time for the information seeker.

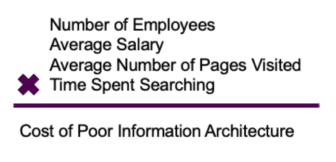

Today, the cost of not quickly finding information is high. The ability to quickly locate information leads to user satisfaction and comfort. This means that when users can find what they need quickly they are more likely to use your platform. In a corporate environment, there is a real tangible cost to not finding information. Here is a simple calculation you can use to calculate the cost of not quickly finding information:

The seconds, minutes, and hours spent looking for information have a clear cost beyond users abandoning the platform in corporate environments.

The Library is a Growing Organism

The final law of library science proposed by Ranganathan states that libraries continually change. In the digital world, no taxonomy effort is ever complete. As user interests and domains of knowledge evolve, so does the need to change the underlying taxonomy. If you are investing in the development of a taxonomy or digital product, you need to accept this and develop frameworks that support the evolution of our information environment. Once the structure of a taxonomy or information environment is completed, following this law is critical. In order to ensure our digital product stays relevant and continues to offer value, we must develop a clear governance framework that allows for the evolution of the taxonomy over time.

Conclusion

The Five Laws of Library Science are as relevant today as they were in 1931. When these laws are applied to a digital environment, we can ensure that the information contained in the environment is easily accessible, audience-focused, and forward-thinking. Although following each of these laws is recommended, at the end of the day, end-user needs are the primary driver of a good taxonomy design. In the face of a clear business case, some of these laws may not apply. If you need help with the design and implementation of a taxonomy that follows these principles, connect with one of our knowledge management experts by contacting Enterprise Knowledge.