Introduction: System Limitations

If you’re reading this, you’re likely already convinced of the value of tags and filters when it comes to creating, saving, and retrieving content. You may even be involved in developing taxonomies at your organization. When working on initiatives aimed at enhancing targeted search and enabling content-level tagging, you’ll find that the systems that house and categorize your content each come with their own strengths and limitations regarding the extent to which they support tagging and filters. We have touched on system limitations in a past blog on Taxonomy Implementation Best Practices, and this blog revisits and expounds upon system limitations in greater detail.

While some fortunate teams have the coveted balance of leadership support, generous budget, and ample time to shop around for a solution that supports robust taxonomy tagging and customizable filters, the reality for most of us entails having to make the best of whatever systems are already in place. Even teams that invest in a Taxonomy and Ontology Management System (TOMS) often have to navigate system limitations when integrating the tool with the existing systems. The systems that consume the taxonomy terms and filters tend to come with shortcomings that pose obstacles to optimal taxonomy implementation. Ideally, the consuming system supports hierarchical facets, captures semantic context like synonyms, supports an unlimited number of tags, and allows for advanced user permissioning, but the reality often falls short on at least one of these features.

To an extent, these limitations should be expected, because the systems in question, be they content management systems, collaboration platforms, or learning management systems, have to fulfill a vast range of business needs. For these systems, tagging or search filters may be one of many desirable features, rather than their core function.

In this blog, I invite two audiences to consider system limitations for taxonomy implementation: firstly, those who have the opportunity to shop around for systems to consume their taxonomy, and secondly, those who have to work around the limitations of the systems they already have in place. While this is by no means an exhaustive list, I’ll discuss some of the main considerations around taxonomy implementation for content management.

System Limitation 1: Hierarchies Not Supported

All too often, systems are unable to support a fundamental element of taxonomies: hierarchical relationships. In these instances, the client finds themselves having to use tags or filters that don’t reflect broader and narrower relationships, and falsely represent very granular and very broad concepts at the same level.

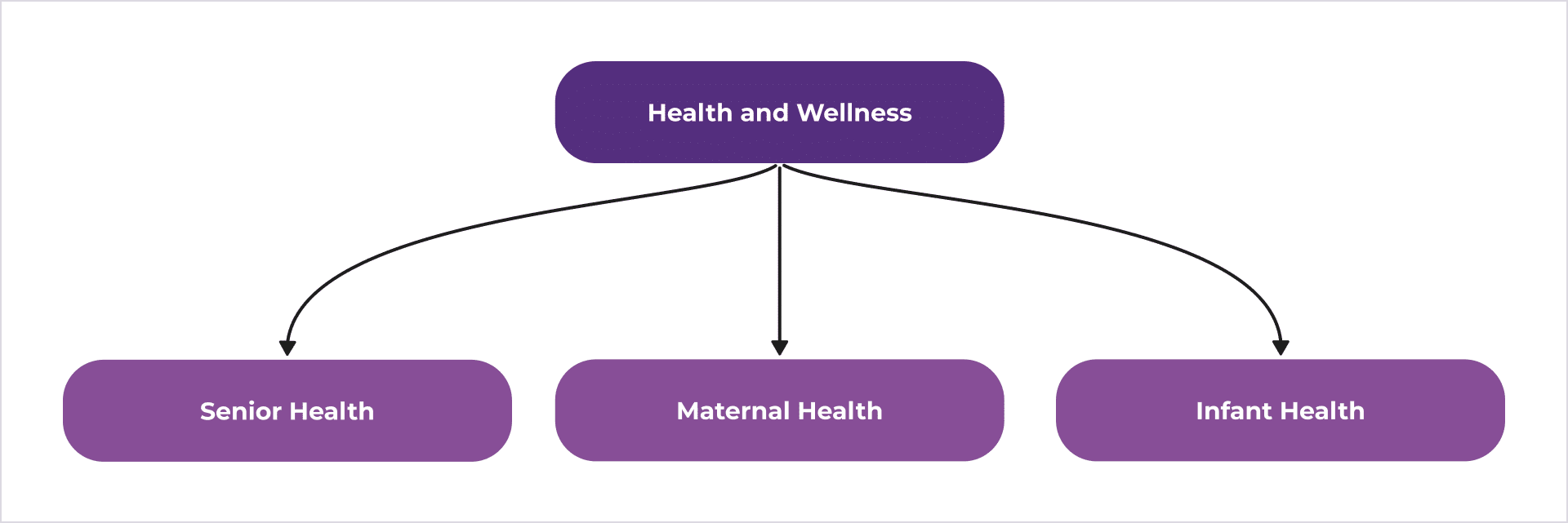

For instance, you may have a tool that supports tagging, which is a great start for making content easier to find, but you aren’t able to indicate that tags like “Senior Health” and “Maternal Health” should be considered more specific than the broader “Health and Wellness” tag (Figure 1).

Why it Matters

The importance of hierarchies lies in the very definition of what separates a taxonomy from a mere controlled vocabulary. Because a taxonomy is a hierarchy of concepts accompanied by semantic context, one of the primary reasons a taxonomy is valuable is because of its ability to express broader and narrower relationships in a human-readable as well as machine-readable format.

Hierarchies are especially valuable for supporting inheritance, in which attributes or properties defined at a higher level in the taxonomy are applied to lower-level elements, and, in turn, whatever qualities are true of the child concept are also true of the parent, or higher-level concepts.

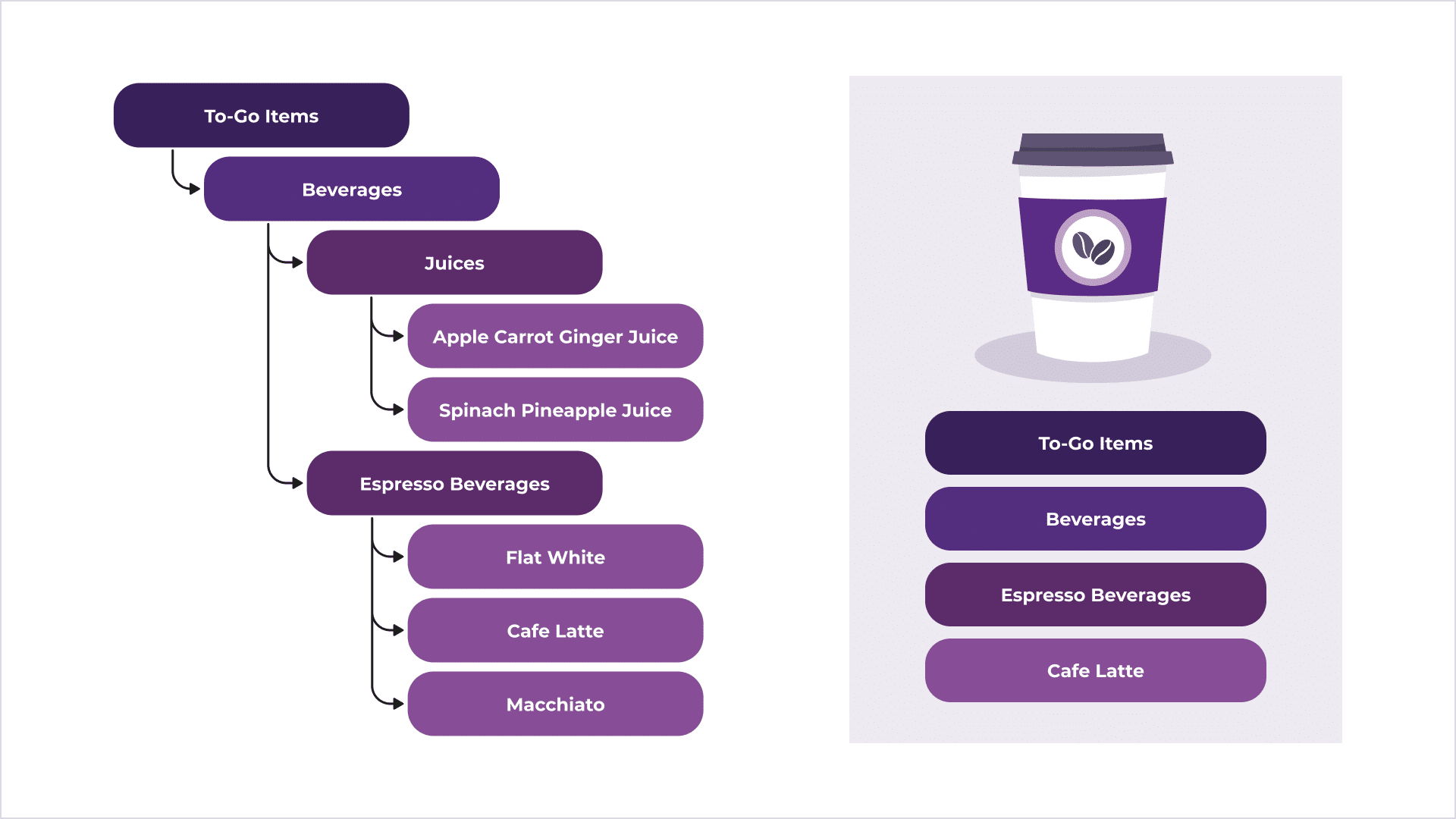

In Figure 2, having hierarchical tagging would mean we wouldn’t have to tag a product with “To-Go Items,” “Beverages,” “Espresso Beverages,” and “Cafe Latte,” because we can see that Cafe Lattes are a type of Espresso Beverage, which is a type of Beverage, which are categorized under To-Go Items.

This can be especially valuable because hierarchical tagging can help reduce the amount of work that has to go into using tags to store and retrieve content, as well as helping the user understand the significance of their tags. Without hierarchical tagging, a user may have to tag a piece of content with both the narrowest concept as well as broader concepts, rather than just apply one tag – which results in excessive tagging, depleting the tags’ value.

Recommendation: Develop detailed tagging guidance to compensate for system limitations, accompanied by an easily-accessible visual of the taxonomy hierarchy for users.

System Limitation 2: Semantic Context Not Supported

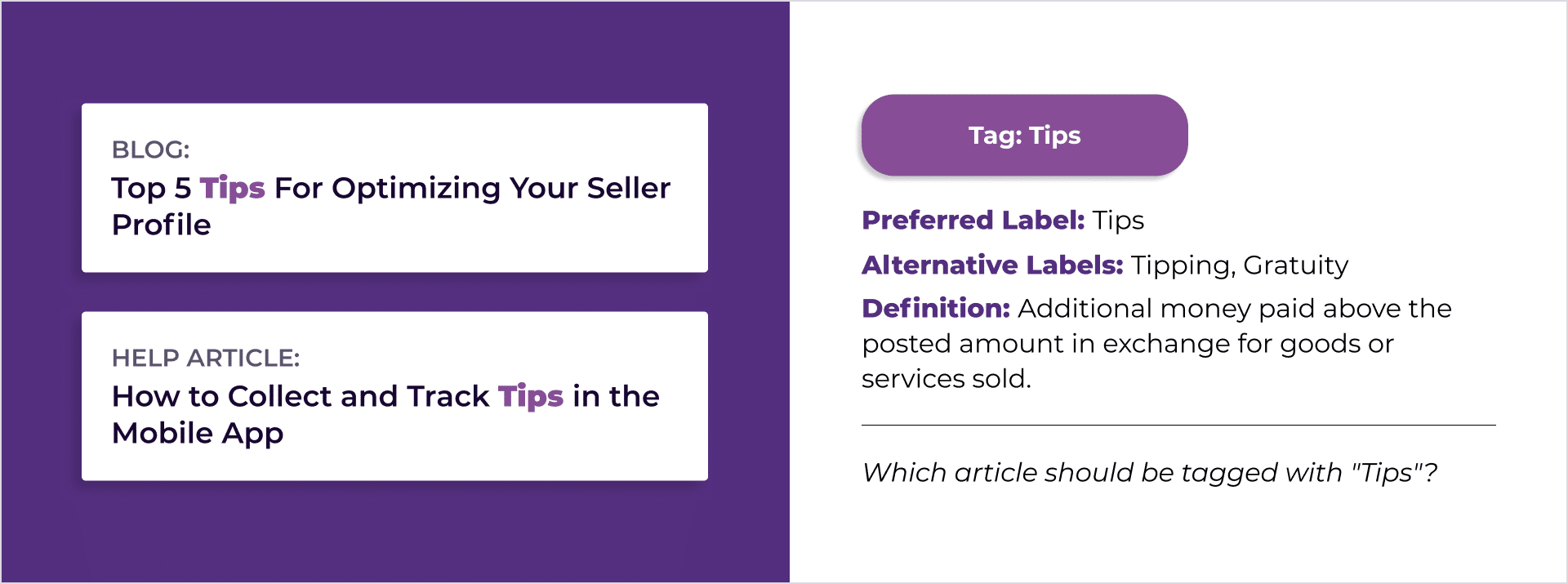

In many systems, tagging – even hierarchical tagging – may be supported, but the tags themselves aren’t accompanied by any additional semantic context to provide additional guidance around what the tag means. For taxonomies adhering to Simple Knowledge Organization System standards, each taxonomy concept (or tag) should include not just the term itself (or, preferred label), but also be accompanied by alternative labels (equivalent terms or synonyms), a definition, and, if applicable, scope notes to provide additional context around intended usage or disambiguation between other concepts. However, many systems lack the ability to store or leverage this valuable context. In many cases, a tag is just a tag, and system users have to rely on implicit knowledge to interpret the broader meanings associated with each tag.

Why it Matters

Although good taxonomy design entails carefully selecting self-explanatory, clear concept labels, there can still be a certain amount of implicit knowledge required to accurately interpret, apply, and leverage tags. Ideally, anyone using a taxonomy should be able to also review alternative labels or scope notes as well as definitions, but this is often unavailable. Alternative labels, definitions, and scope notes are essential for documenting otherwise implicit knowledge that, without which, could result in tags being inappropriately applied to content. This can result in undesirable outcomes like scope drift, incorrect tagging, and more.

The semantic context provided by a robust taxonomy is also essential for future-proofing a taxonomy. With industries experiencing greater degrees of uncertainty and worker turnover, it’s more important than ever to avoid taking institutional knowledge for granted. For instance, a team may be initially aligned on the terminology and meaning for a taxonomy of 50 concepts, which are also tagged to content. However, let’s say that the team responsible for the taxonomy undergoes a reorganization at their company, and some individuals move to different teams, others retire, and others move to another company. Whoever inherits ownership of the taxonomy may no longer have access to the knowledge that contextualizes the meaning of those taxonomy terms. Over time, the terms lose their meaning, and are subject to different interpretations and usage.

In Figure 3, we can see that both pieces of content (a blog and a help article) mention “Tips.” Without the additional context provided by the alternative labels and definitions, it would be reasonable to have both pieces of content tagged with “Tips.” However, being able to access this context reveals that only the second article should have this tag.

As illustrated in Figure 4, suppose a company isn’t consistent about using the term “Seller Protection” or “Merchant Protection.” Perhaps the Legal team calls it “Merchant Protection,” but customer-facing content tends to say “Seller Protection,” and internal customer support workers refer to it as “Merchant Protection.” In a case where content has to be manually tagged, just having a tag for “Seller Protection” without also indicating that “Merchant Protection” is an equivalent term would result in content not being tagged, even when it should be.

Recommendation: Ensure that key semantic context such as alternative labels and definitions is available to users, highlighting areas of frequent confusion.

System Limitation 3: Tag Number Limits

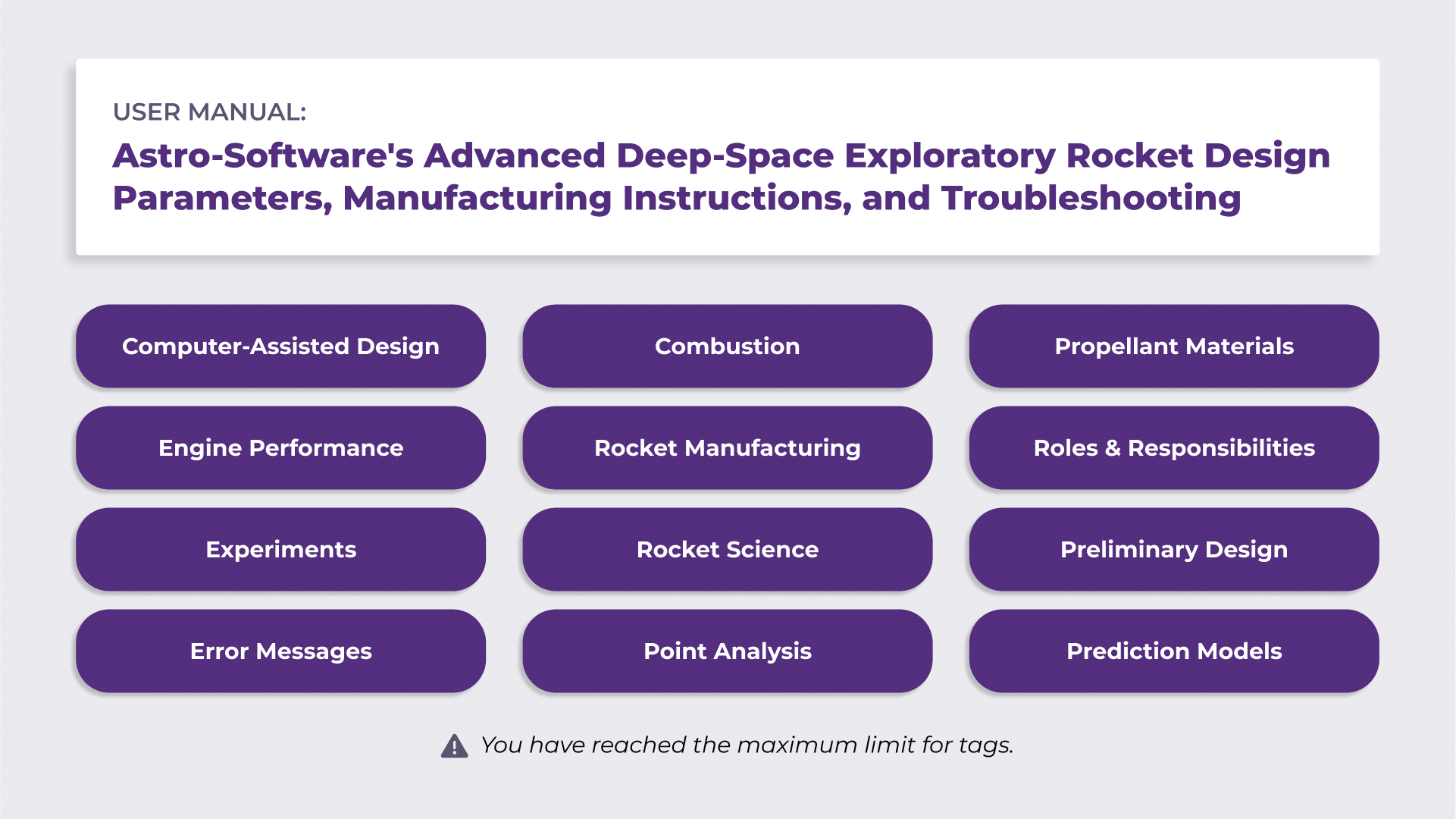

Another issue that users frequently encounter is where a system supports tagging, but imposes limitations on the quantity of tags supported. These limits primarily manifest themselves in two ways: firstly, by imposing a limit on the total number of tags that the system can support, or secondly, putting a limit on the number of tags that can be applied to a single piece of content. Some systems may impose both kinds of limitations.

Why it Matters

Generally speaking, limiting the number of tags you maintain in your system can actually be one of many ways to adhere to best practices in taxonomy. We frequently encounter situations where the number of tags within a system have proliferated well beyond a manageable quantity, and users may only meaningfully engage with several dozen tags out of thousands. In these instances, we often find that many of the tags are duplicates, represent concepts that are no longer applicable or relevant, or go into an excess level of granularity. However, there can be situations in which a higher number of tags may be necessary, such as when a particularly diverse range of content or data needs to be retrievable and a certain degree of specificity is required to ensure precision in search.

In one instance, we worked with a client using a CMS that could only allow for a total of 15 tags to be assigned to a single piece of content. While, in most cases, 15 tags or fewer would be an appropriate maximum number of tags to assign to a document to avoid over-tagging, this limitation could be problematic for long-form content, like complex user agreements or long scientific articles. In another instance, a system could only support 500 total tags – which would be appropriate enough for a repository of simple help articles, but may be insufficient for a database of complex healthcare topics.

Suppose a content repository houses hundreds of long, highly complex user manuals like the one shown in Figure 5. However, the content repository only allows for 12 tags to be applied to any given content item. In this situation, a 12-tag limit would be woefully inadequate.

Recommendation: Explore ways to accompany complex documents with additional context to complement the limited tags.

System Limitation 4: Inadequate Options for Roles and Permissions

When implementing a taxonomy with a system, whether that means configuring search filters or tagging content, it’s crucial to be able to configure user roles and permissions. On many teams, content roles are distinct; you have content strategists, content authors, content managers, a taxonomist, and so on. Furthermore, a mature taxonomy requires governance, where well-defined roles dictate who is responsible for deciding upon and carrying out updates to a taxonomy, and effective governance is difficult to achieve without a system that supports distinct permissions to accompany these defined roles. However, not all systems have customizable roles to support governance or even basic taxonomy management. In some cases, new tags can be freely entered, or anyone can have the ability to apply tags to content.

Why it Matters

Anyone who’s been involved in content tagging knows how challenging it can be to successfully guide a group of taggers to consistently tag content the same way. Some may take an exhaustive approach, tagging content with concepts that may only be tangentially relevant or only mentioned in passing. Others may be more cautious, only applying tags when a concept acts as one of the core themes of a piece of content. While drafting detailed tagging guidelines and providing robust tagging training can go a long way in mitigating these differences in tagging approaches, this is not a foolproof approach.

These issues can be only further exacerbated when systems allow for any individual to add new tags to a system without any formal governance review. In one instance, we worked with a nonprofit client where it was easy to add new tags to a system, and over time, the total number of tags grew to over 2,000. In another case, at a large financial technology organization I worked with, there were no system limitations on how many entries could be added to a drop-down menu of customer contact reasons, which resulted in a list of over 1,400 entries, the majority of which were duplicates. In situations like these, tags lose the value they were meant to provide, and may even foster more confusion than if there were no tags at all.

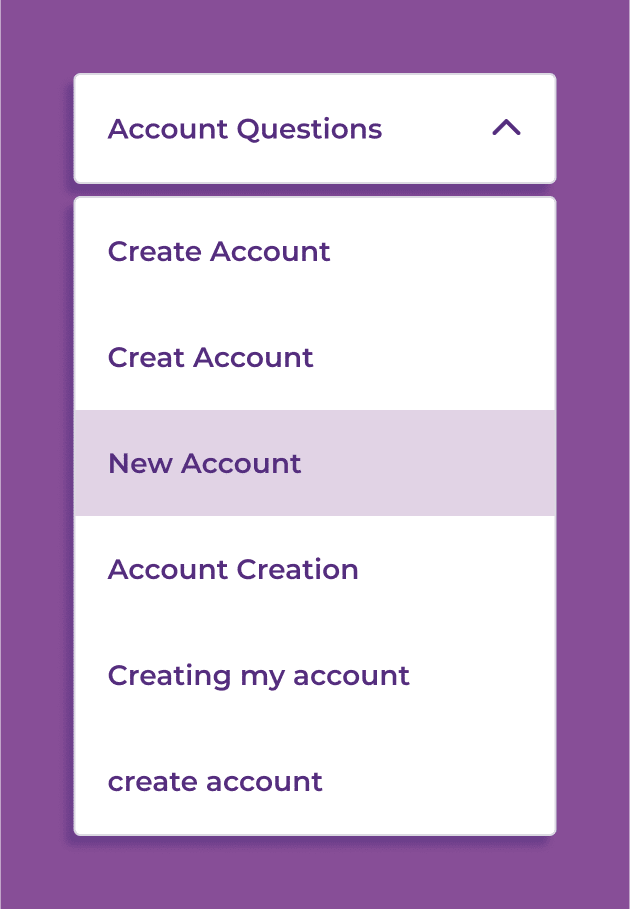

In the example shown in Figure 6, a system where any users can create a new filter or tag without any user roles restricting permissions can easily lead to a proliferation of overlapping or duplicated terms. Here, we see a drop-down menu of “Account Questions,” where users were able to create new tags without having to review which tags are already in place, resulting in six different selections about creating an account. Lack of controls around tags or filter creation can quickly result in an unwieldy tool that is difficult to use. If tags or filters become bloated enough, users may even select a random term or only pick the top term rather than scroll through hundreds of entries.

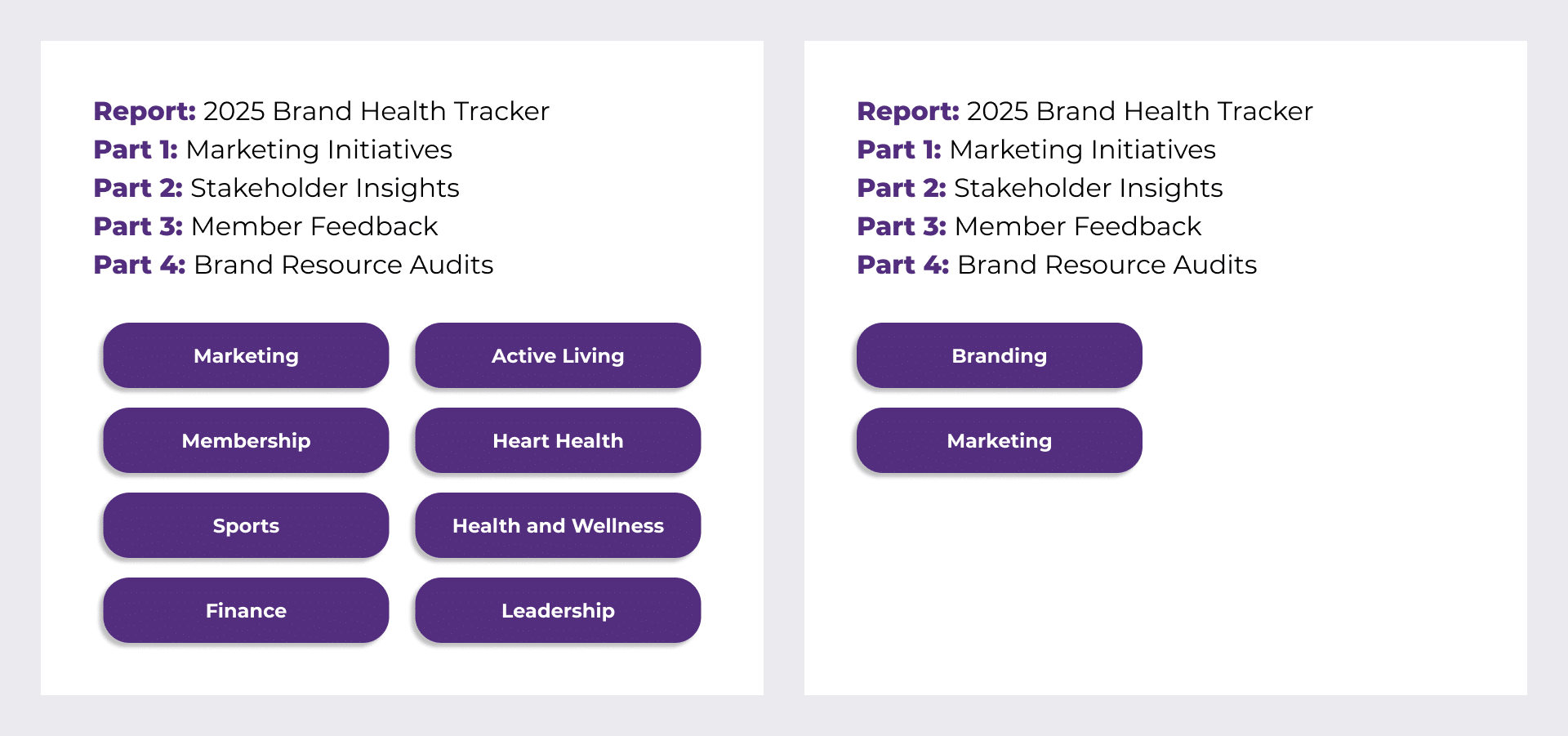

Figure 7 illustrates a situation where two different content authors were asked to tag content. On the left, one tagger got carried away, providing far more tags than were necessary, and misinterpreting “Brand Health” to mean physical health. On the right, a different tagger was more strategic and selective, and only applied tags that would be necessary to retrieve the intended report. User controls help ensure that only qualified individuals can create, apply, and manage tags, and are essential to prevent an uncontrolled proliferation of tags, enable consistent tagging, and support ongoing governance.

Recommendation: Provide detailed tagging guidelines as well as training to ensure aligned approaches. For systems where new entries can be freely added, communicate frequently about the importance of preventing accidental entries, and schedule frequent clean-ups.

Conclusion

When navigating the transition from designing a taxonomy to implementing it in the intended systems, it can be common to encounter a gap between ideal implementation (hierarchical tagging without system-imposed limits, controlled by tight role-based user permissions), and reality. A certain degree of flexibility, creativity, and above all, effective documentation will be necessary to develop effective strategies to get as much out of your taxonomy as possible in spite of any challenging system limitations. Developing a detailed set of use cases that the taxonomy is intended to address is essential, so you can evaluate which system limitations are acceptable and which should be considered deal-breakers for the success of your project.

Are you in the process of implementing a taxonomy at your organization, but struggling to navigate any of these system limitations? We have extensive experience navigating these system limitations to guide organizations to successful, impactful taxonomy implementations, and would be happy to help. Contact us to learn more.